Welcome to Lady Chef Stampede, Amanda Cohen’s series about the world’s most influential Lady Chefs! Click here to read her Q & A with us about the column, or read on to learn more about this week’s Lady Chef…

This week’s Lady Chef Stampede singles out a lady who is not a chef, but a cookbook writer, Mary Vereen Huguenin. I’m making an exception this week to celebrate Charleston, SC, home of Ted and Matt Lee who I’ve known for a long time and whose new book, Charleston Kitchen, just came out (also, full confession: I stole a bunch from their book for this entry).

You think your restaurant is local? Check out this recipe, “Arise early and go on the Lake and catch about eighteen Big-Mouth Bass, Bream, or Red Breast. Have ‘Patsie’ make an outdoor fire of pine bark, then have her slice about one dozen Irish potatoes and about one dozen small onions…” Or “Drop live cooter in a pot of boiling water,” which is the first step in making Bluff Plantation Cooter Pie. Looking to prepare Mrs. Alston Pringle’s Calf’s Head Soup? “Remove brain from calf’s head,” it begins. “Wash head thoroughly and boil in four quarts of water until tender.”

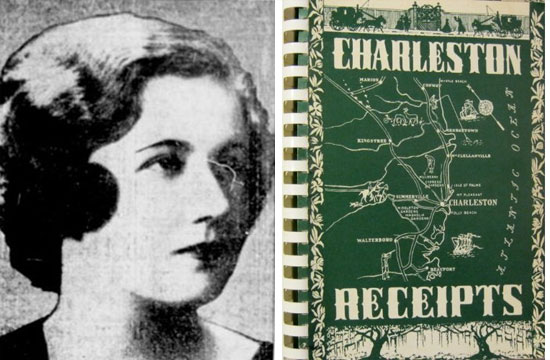

This aren’t antique recipes I dug up from some ancient cookbook, but the recipes from Charleston Receipts, first published in 1950 and still in print today, it’s the oldest continuously published Junior League cookbook and it’s the benchmark for spiral-bound community organization cookbooks everywhere. Having printed close to a million copies of the book since it first came out, and having raised over a million dollars for 40 charities in Charleston (including the Charleston Speech and Hearing Center, Comprehensive Emergency Services, and the restoration of the Charleston Museum Library) the success of the book rests entirely at the feet of Mary Vereen Huguenin.

There’s an archaic feel to this cookbook, larded with out-of-date bits of Gullah folklore and a painful reproduction of African-American dialect. The fact is, most of these dishes were originally designed not to be cooked by the women themselves, but by their “help.” Then there are the receipts, many of which have been forgotten today. Among all the chafing dishes, ring molds, jellies, and aspics there are Hobotees, Ratifias, pilaus, Philpys, Syllabubs, and Cubillons. It’s like a museum of forgotten food terms. Surprisingly, the recipes work. I’ve made the Cheese Straws and you’d be hard pressed to find a more foolproof recipe. But more than that, as the Lee Brothers write in their new cookbook, “The many threads of English, African, Huguenot, Portuguese, German, Polish, and other ethnic influences on Charleston are palpable in its pages (even if chapter headings and headnotes register as lily white in perspective).” It’s a an outline of the history of traditional Lowcountry cooking coming at a time when so much culinary history has been forgotten, whitewashed, retold, or appropriated. It’s a living library that preserves the roots of Southern cooking.

Shockingly, Huguenin wasn’t born in Charleston. She was born in Moultrie, GA to a “distinguished Hugenot family” as the paper said. Fortunately, in 1932 she married a Charleston man and moved to Halidon Hill Plantation, an old rice plantation which she set about restoring. She joined the Junior League of Charleston, and in 1948 two of the younger members (Martha Lynch Humphreys and Margaret B. Walker) published 2000 copies of Charleston Recipes which contained about 400 recipes.

Apparently it sold well, and the older members of the Junior League got interested. With Mrs. Huguenin in charge, they solicited 750 recipes from their members and other esteemed Charlestonians, then spent two months testing and adjusting them. Every recipe was either named after the contributor, or they were listed (along with their maiden name) below. Mrs. John Simonds (formerly Frances Rees) contributed Mrs. Alston Pringle’s Mock Terrapin Soup, Mrs. Laurens Patterson (Martha Laurens) chimed in with Mrs. C.C. Calhoun’s Chafing Dish Oysters, there was Sweet and Sour Pork from a dinner given for the husband of Mrs. Louis Y. Dawson, Jr. (formerly Virginia Walker) by one of the Soong Sisters herself while he was stationed in China, and so on in an endless litany of Charleston families.

The book almost didn’t happen. The Junior League’s original print run was for 2,000 copies and some of their husbands worried that they’d never sell that many. They sold out in four days. In 1951 alone they went back to print three times. Every other year, the Junior League would print about 25,000 copies and then, in the early 80’s, they started turning out 50,000 copies at a time. Overseeing it all was Mrs. Huguenin who devoted her life to being its chief advocate, protector, marketer, and tireless promoter. In doing so, she made herself the custodian of the heritage of Charleston cooking. When White Trash Cooking lifted seven recipes in 1986, she and the League sued, later settling out of court. It probably almost killed her to have 50 years of her life’s work called “white trash” in print.

Mrs. Huguenin’s husband died in 1988, and when Hurricane Hugo hit the following year she chose to weather the storm alone at her beloved Halidon Plantation. The next morning she woke up to find that it had leveled 70% of the trees on her property. Five years later, in 1994, she died at Halidon at the age of 84. Charleston’s Post and Courier paid her the ultimate qualified compliment in its editorial page to mark her passing, “Although not born in Charleston, Mary Vereen Huguenin came to represent all that is gracious and stalwart in her adopted city.”

You can still buy a copy of Charleston Receipts and it looks almost exactly the same as when it was first published. There’s something reassuring about this kind of continuity – a cookbook made of recipes passed down from cooks to their employers, from mothers to their daughters, from grandmothers to their grandchildren. The copy I own? It’s part of that chain, given to me by my mother-in-law who was given this copy back in 1980.

Amanda Cohen is the chef and owner of Dirt Candy, the vegetable restaurant in the East Village. Her award-winning graphic novel, Dirt Candy: A Cookbook, is the first graphic novel cookbook in America, and it’s cheap, so you should buy ten copies.

Previously in this series: Where Are All The Female Sushi Chefs?

Have a tip we should know? tips@mediaite.com