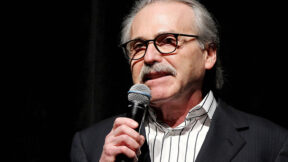

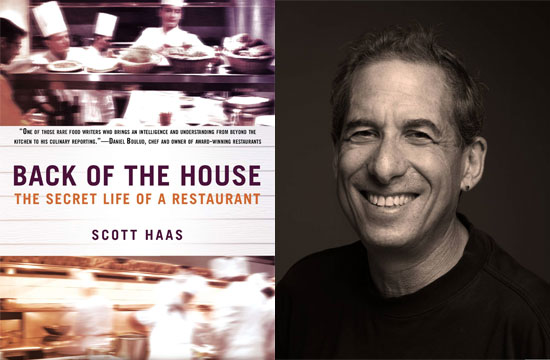

Food Writer Scott Haas On Tony Maws, Boston, And What It Means To Be A ‘Great Chef’

In his upcoming book Back Of The House: The Secret Life Of A Restaurant, writer and psychologist Scott Haas goes into the kitchens of Boston restaurant Craigie’s On Main for a full year, in an attempt to understand how a restaurant — menu, kitchen, front of house, even the diners — reflect the mind of Tony Maws, the idiosyncratic chef at Craigie’s helm. The results — with detours into the kitchens of Andrew Carmellini and Daniel Boulud — not only paint a portrait of one of America’s most wildly creative chefs, but dares to ask the question: can an overabundance of creativity, even in the hands of the most gifted chefs, backfire? We sat down with Haas to get his thoughts on his book.

I was wondering what you felt about that first meal [at Tony Maws’s restaurant Craigie On Main], where you came in with expectations of one thing and left stunned. Were you familiar with the way food had changed in New York, and did you expect to see that evolution in Boston?

I’ve been writing about restaurants for over 20 years, [so] I’m very familiar with it. It’s just — it’s really a matter of preference in some ways. On a personal preference level, I really love four kinds of cuisine, basically. I love French, any kind of French cuisine, rustic or classic. I love Italian and Italian-American, and I love Japanese. And that’s about it. I mean, I don’t mind other cuisines…but on a personal level, the kind of food I like…it’s just a matter of preference. I’m not really into pork, or offal. I’m not into the chef being the center stage, or so creative that it overshadows a canon or a tradition.

So that was your paradigm when you walked into Tony Maws’s restaurant — and then he changed it simply by being creative. You go into detail about that more in the book, but essentially, is that what prompted you to follow him for a year and chronicle his restaurant?

Contextually, in terms of the Boston dining scene, there is certainly no one doing anything more interesting than what he’s doing. He’s really, in a lot of ways, trying to raise the level of cooking, raise the level of what goes on in kitchens in Boston. It’s unfair to say, but until recently, let’s say ten years ago, you had two kinds of restaurants: the restaurants that students went to, and the restaurants that students went to when their parents were in town and could pay.

And it evolved to the point where the chefs got so creative, as to be like “Who could be more creative than the next chef?” So instead of serving at L’Espalier a cut of venison, a traditional, proper cut of venison, the chef there would do a cocoa butter reduction with the venison. “Do we eat this or not?”

Gosh, did that taste like a mouthful of lotion?

It got to the point where chefs were being celebrated for their creativity. Now, there’s not a single chef in the city of Boston who was carrying on a particular tradition rooted in personal experience growing up in another country. There’s only two chefs who come relatively close: Raymond Ost [of Cambridge’s Sandrines], and [Jacky Robert,] who runs Petit Robert Bistro. There’s no Daniel Boulud; there’s no…

There’s no “Great Chef”?

You can say that if you want to! I’m not going to say that. There’s a lot of chefs who aspire to greatness. And the book is not about whether New York is a better dining scene, or Boston’s a better dining scene. To me, the book is about the psychology of a chef who puts his personality into the foreground of his cooking.

When [Tony’s] not in the restaurant, there’s a sense that he has that things are not going to run as smoothly. And that’s a very different mentality than so many chefs in other cities around the country, who operate on the basis of teams run by executive chefs. I think there are a lot of really good restaurants in Boston, but I think it’s extremely complicated as to why some of the restaurants in Boston have not reached a level of parity with restaurants in other cities. It’s really not for me to say whether or not they have achieved the parity; it’s a really personal opinion. If you ask any chef in Boston whether or not they’re as good as chefs in Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, Las Vegas, they will allege that they are. And I don’t know. Maybe they are, maybe they’re not.

But the real issue is that the creativity of the chefs in Boston has taken the center stage, compared to an effort to perfect a certain cuisine….You go to a place like Craigie on Main’s, and it’s not specific to anything. Tony is of the opinion that his place is more like Wylie [Dufresne]’s place, or David Chang’s place, or the guys who run Roberta’s. It’s the idea that his cuisine is a reflection of a global mentality: a chef who doesn’t have rules, and operates on the basis of what he enjoys, and what he thinks would work. That’s a really dicey proposition. It’s a proposition based on imporvisation rather than consistency.

You’re one of the few food writers who I’ve read and spoken to who looks at a chef’s menu with a comprehensive look at the chef’s life and personality. How much does your background in psychology play into this analysis?

Absolutely, a hundred percent. My argument is that if you go to, say, Per Se or Daniel, they’re both spectacular restaurants. But the personalities of the chefs, whether they’re in the room or the kitchen — or not — really pervades what is coming out of the kitchen. For example, at Per Se, you get this highly disciplined, food-specific kind of dining experience. It’s an awesome experience — literally, you’re supposed to be in awe of what you’re eating, you’re supposed to be in awe of the room. It’s almost like a cathedral type of thing… I don’t think that was Thomas Keller’s intention, but that’s what happened, because the disciplie that was necessary to create food that perfect somehow extended to the front-of-the-house mentality. Whereas at Daniel, the food is not perfect, it’s more refined-rustic French. And so it’s really like you’re at a party. It’s more joyous to be there. And when you’re at Per Se, it doesn’t feel joyous. I think that’s a reflection of the chef’s personalities.

And you definitely saw that principle in action at Craigie’s On Main?

Tony’s personality at Craigie’s on Main is the whole story of that restaurant. In a lot of ways, he doesn’t really have a particular tradition to rely upon. He didn’t grow up in a household or a country or a neighborhood where food was a prominent part of his upbringing. He didn’t work for a long period of years in a three-star Michelin restaurant. He worked chiefly at East Coast Grill, which is a terrific American restaurant that serves barbecue, and then shifted over to Fish and Shellfish, run by the extremely talented Chris Schlessinger. Then he worked for many years at Clio, which is relatively French and run by Ken Orringer. But Ken is someoen who also has a Mexican taco restaurant, a “pull up your sleeves and eat” Italian restaurant, and he’s got the Spanish restaurant Toro, [which is soon moving to New York].

So, Tony in a lot of ways has the opportunity to rely on a lot of kitchens, but not one specific kitchen…and in a lot of ways, his food is a reflection of his personality. All of the great restaurants are reflections of the chef’s personality. But the difference is, in my opinion, if you go to a Batali restaurant, Mario doesn’t have to be there. He’s got a crew, and a team that understands his sense of purpose and sense of mission. And [that mission] is really an incredible commitment to the very best Italian ingredients and the very best Italian elements of cooking. That’s not the story of Craigie’s.

Actually, when you say that, it brings to mind some of the big-name, TV, capital-C “celebrity chefs” in New York City (for instance, Guy Fieri), whose personalities are sometimes just emblazoned on the door. Do you think there are more branding opportunities for those kinds of chefs, given your previous train of thought?

I was wondering about that, actually. You know, when you have a branding opportunity like Daniel, who now has four different levels of restaurants: the fine dining, the cafe, the bistro, and the downhome place, DBGB. Those, to me, make more sense in terms of branding, because when you walk into one of Daniel’s restaurants, you can make it pretty clear, if you’ve done a little bit of reading, that’s what you’re gonna get. The difference between Tony and Daniel is that Daniel — I’ve known Daniel for about eighteen years, and if anything he is extremely consistent. Tony is not extremely consistent. Tony’s food varies from night to night. Daniel will do that — if there’s a VIP in the room, Daniel or his executive chef will add things to the tasting menu. Tony will literally change things night to night. He does this to keep his cooks from being bored — or to keep himself from being bored — but it creates challenges for the branding, because if you have a brand that’s characterized by a continuously changing approach to what’s on the menu, then how do you create a brand in Chicago based on that kind of concept?

I went to Daniel’s restaurant in Vancouver, Canada and I could have been in New York. It was just brilliant, brilliant French food. I’m not sure opening Craigie On Main in Vancouver would be as easy, because [Tony] wouldn’t be there. That may change. That may evolve. He’s opening a second restaurant within a year, that’s kind of a relaxed, down-home kind of place. Maybe that will create a brand for him…

Tony likes to shake things up, and that’s clear to me in how he does things in his restaurant. But there’s a lack of consistency. So on the one hand, he has this idea where he doesn’t want to serve any Californian wines, because he doesn’t want people to have familiar wine. He only serves wines cheifly from France, some from Italy. But on the other hand, he serves all these beautiful craft beers, chiefly from the United States. So why is it all right to sell beer from the states, but not wine? That doesn’t make any sense to me. When he talks about wanting to use all local products, why is it that he buys his olive oil from Lebanon? If he talks about doing things from scratch, why is he getting bread from Iggy’s Bakery, a commercial bakery whose bread you can buy at Whole Foods?…I think he’s a work in progress. I don’t think he’s clearly defined what he wants to do, or what his kitchen wants to do.

So you’re saying that that consistency and that sense of direction, for him, are necessary to reach the next level of prominence in the food world?

Yeah, it feels that way to me…It’s challenging for the cooks and chefs within Craigie to really know what the rules are, because the rules keep changing…Even a chef with one restaurant, like Gordon Hamersley’s restaurant Hamersley’s Bistro in Boston, which is a terrific, small, French-style bistro, Gordon said to me years ago that he thinks his restaurant is successful if people enjoy the food and he’s not there. I think he’s right…The concern that some chefs have is that this means it’s going to “Disney-fy” the restaurant. I think that’s incorrect. That’s not the way to look at it. The guy who designed the BMW you’re driving around with — it’s a good car! You don’t need to have the original engineer make that car. You need to have teams of people who understand what the rules are, and follow the rules. It’s really pretty simple, if you think about it.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Have a tip we should know? tips@mediaite.com